2 of the Most Commonly Overlooked Muscles Injured with Whiplash Associated Disorder and Why Neuromuscular Therapists Will Address Them

ANMT Program Founder Cynthia Ribeiro working on the posterior neck muscles

About Whiplash Associated Disorder

“Whiplash-associated disorders (WADs) are a common, disabling, and costly condition that occur usually as a consequence of a motor vehicle crash (MVC). While the figures vary depending on the cohort studied, current data indicate that up to 50% of people who experience a whiplash injury will never fully recover and up to 30% will remain moderately to severely disabled by their condition.”1

Because WADs are incredibly complicated musculoskeletal conditions, the management is tricky to say the least. Many experts debate the etiology of whiplash and the diagnosis and evaluation of the related structures is nearly impossible. “It can be stated that “whiplash” is an oversimplification of the complex forces that occur. These forces occur when there is a rapid head acceleration that is sometimes 2 to 3 times greater than the vehicle and results in injury to the internal structures of the neck. Previous studies have described these as tensile, compressive, shear, and torque forces.”2

The forces typically experience with a whiplash injury are numerous. One must consider the contractile tissue, inert tissue, and bony structures involved. Additionally, the patient’s previous health and injury history complicate matters which would validate the thought that whiplash injuries are like snowflakes; they are all unique which makes them even more challenging to manage.

Most will agree that the contractile tissue most commonly affected by whiplash include the scalene, splenius capitis, sternocleidomastoid, upper trapezius, posterior neck muscles, and pectoralis minor. “There has also been a substantial body of research investigating the motor, muscle, and sensorimotor changes in individuals following whiplash injury. Changes include loss of movement, altered muscle recruitment patterns, morphological changes in neck muscles, disturbed eye movement control, loss of balance and joint repositioning errors, and decreased muscle strength with most of these changes being identified in the early acute post-injury stage as well as in individuals with chronic WAD.”1 Given these effects to the soft tissue there are multiple interventions that can be applied. From a Neuromuscular Therapy perspective, there are additional considerations. “There is now overwhelming data demonstrating the presence of sensory disturbances in patients with chronic WAD. These include decreased pain thresholds to various stimuli including mechanical pressure, thermal stimulation, electrical stimulation, and vibration. Decreased pain thresholds or sensory hypersensitivity have been demonstrated both locally over the neck as well as at more distal or remote sites such as the upper and lower limbs where there is no tissue damage. The absence of tissue damage at the site of testing suggests that a central sensitization of nociceptive pathways is the cause of the pain hypersensitivity.”1

The First Muscle

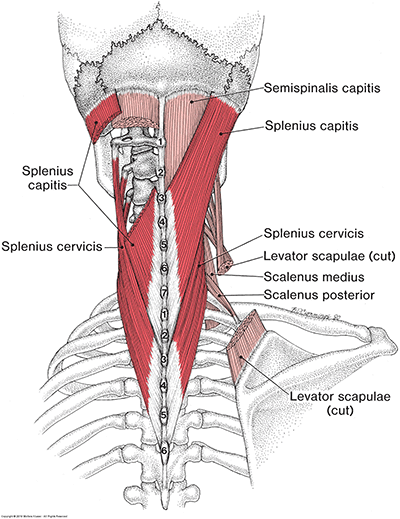

Splenius Capitis and Cervicis muscle – Figure 15-13

The first of the two muscles that are commonly overlooked during WAD is part of the posterior neck muscles. Many will focus on the posterior neck muscles that attach to the cranium.; semispinalis capitis, splenius capitis, upper trapezius, and some will throw in levator scapula into the mix even though it does not attach to the cranium. The muscle of concern is the splenius cervicis.

The general superior attachment is located on C1-C3 and the inferior attachment is found on the spinous processes of T3-T6. Given the understanding that the mechanism involved in WAD injuries includes flexion and extension at high velocities, one can observe the method in which his muscle will be quickly over lengthened followed by a severe contraction. Splenius cervicis will produce extension of the neck when it contracts bi-laterally. Functionally it assists controlling flexion of the neck. Whether the muscle is involved with rotation and lateral flexion can be debatable; however, when considering the effects of the forces experienced during whiplash, it can be observed that not only could subluxation of the involved vertebrae alter the action and function of this muscle, “(t)here is now much scientific data available to indicate the presence of disturbed nociceptive processing, stress system responses, muscle and motor changes as well as psychological factors in both acute and chronic whiplash-associated disorders.”1

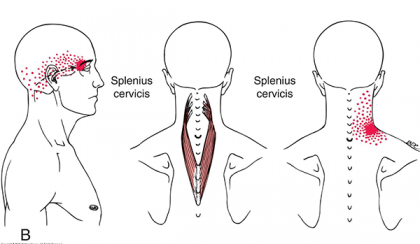

Splenius Cervicis Trigger Point Referral – Fiugre 15-2B3

Aside from threat signal processing from the nociceptors, pain referrals from the splenius cervicis and the autonomic phenomena associated with trigger points found in the muscle can prolong the pain and symptoms experience with WAD. The pain arising from the trigger points found in the upper portion of splenius cervicis is typically described as diffused through the inside of the head with tends to feel greater behind the ipsilateral eye and sometimes into the ipsilateral occiput. The trigger points found in the lower portion of the splenius cervicis refer pain superiorly to the base of the neck and can merge with the trigger point referral zone of levator scapulae. Dysfunction in splenius cervicis can also contribute to blurred vision of the ipsilateral eye without dizziness or conjunctivitis, (reddening of the eye).

The Second Muscle

While whiplash injuries are focused on sprain and strain within the neck; WAD includes conditions that are caused by the initial neck injury. One of those conditions is Temporomandibular Joint Disorder. “Temporomandibular disorders due to whiplash can be described as a group of signs and symptoms related to the Temporomandibular Joint, (TMJ) and the muscles of mastication in patients who have received a traumatic cervical extension-flexion (extrinsic) injury, but who have not had direct physical injury to their jaw.”2 Whether Temporomandibular Joint Disorder, (TMJD) is caused by whiplash or not is a matter of debate. Based on several studies, a major distinction needs to be considered when associating TMJD to WAD. Some studies found that TMJD wasn’t related to WAD while other studies found a correlation; the main difference between these studies is that those that found no correlation focused on the acute stage of injury; while those that indicated a relationship between the two disorders focused on the maturation/chronic aspect of WAD. This would lead one to believe that, if the muscles of mastication are addressed in the acute stage of WAD, it is possible to prevent any TMJD issues to arise. Typically, the TMJD symptoms may be ignored or may not even be recognized due to the more serious nature of injuries related to whiplash. It is only after those initial injuries have been address that TMJD symptoms may present themselves. One conclusion found that 33% of those that experience whiplash trauma developed delayed TMJ dysfunction and/or pain during the first year post accident.

Going back to the forces that are experience during whiplash; there are two theories that describe the mechanism of injury that may create TMJD, those are the Direct Injury Theory and the Indirect Injury Theory. The Direct Injury Theory proposes the extension and flexion of the neck occurring simultaneously with jaw movement creates a shearing stress and compressive force on the retrodiskal tissue; this is directly related to the hyperextension aspect of whiplash. Meanwhile the indirect theory considers force which lengthens the lateral pterygoid in conjunction with the force generated from the accident can stretch and posterior attachment of the articular disk. This mechanism becomes more significant if the trauma occurs with an open mouth when the tissue is already stretched; “whiplash-induced myospasm leads to abnormal jaw posturing and parafunctional activity that results in eventual dyscoordination and internal derangement. Other indirect mechanisms may include postinjury stress, cervical postural changes, and postural imbalance.”

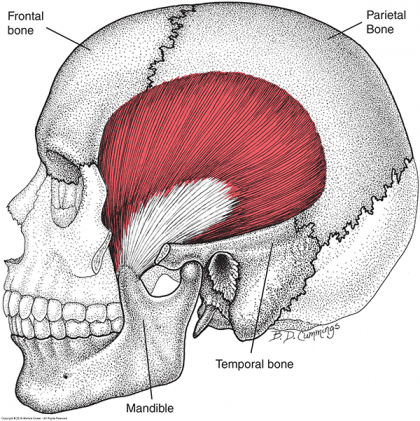

Masseter Muscle – Figure 9-13

The primary muscles of mastication are:

- Masseter

- Temporalis

- Lateral Pterygoid

- Medial Pterygoid

The muscle that typically is overlooked in WAD is masseter. Attaching to the zygomatic arch and the mandible, the masseter is responsible for elevating the mandible and the deeper fibers retract the mandible. The point of interest involves opening and closing the mouth. During these movements, flexion and extension of the neck also occurs.

As the mouth opens, the cranium will rotate posteriorly which creates extension of the neck. The exact opposite movement occurs while closing the mouth. Alterations in this synergistic relationship with the posterior cervical muscles can alter movement patterns and increase risk for musculoskeletal pain in the head, neck, and jaw.

The Relationship

Given the typical amount of flexion and extension within the atlanto-occipital joint is approximately 5°, and the attachment of splenius cervicis to the first three cervical vertebrae; any movement that goes beyond the typical range of motion allowed will put strain on those muscles. Noting now that there are small degrees of flexion and extension of the neck during mastication, any disruption to the posterior muscles will affect the actions of masseter. The additional force that masseter may have to produce to complete its actions create the potential for exertion of a muscle that is dysfunctional and the motor pattern created will continually strengthen that particular dysfunction.

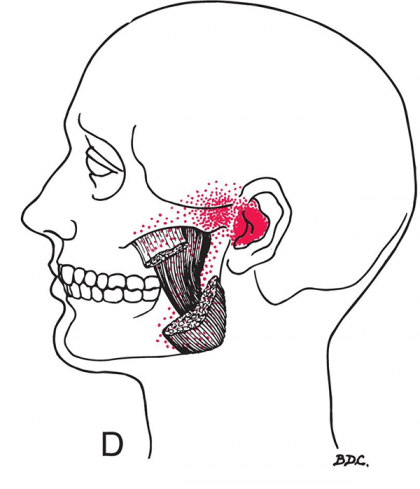

Masseter Deep Muscle Belly Trigger Point Referral – Figure 8-23

Both splenius cervicis and masseter have trigger point referrals affecting the ear. Should this pain create symptoms such as tinnitus or altered vestibular system functionality, dizziness, vertigo, lack of balance will all be exacerbated and prolonged even after the major injuries from a whiplash have subsided. Perpetuating these symptoms can lead one to conclude their injuries have not healed and may contribute to additional productivity decreases and medical costs.

Neuromuscular Therapists work towards supporting the rehabilitation programs prescribed by other health care providers. Addressing the pain referrals and other manifestations of the myofascial dysfunctions will improve the successful recovery of those experiencing WAD. Neuromuscular Therapy should also be considered a preventative solution. Should a patient present with WAD, to alleviate the progression from an acute injury into chronic, addressing the splenius cervicis and masseter will only support their efficient rehabilitation. Many researchers will agree that current management of WAD are in need of evaluation to more efficient solutions. With 50% of those experiencing WAD unlikely to ever recover; one must consider the sources of dysfunction are not truly addressed. Assisting those patients to restore functionality and performance by addressing these two muscles along with many others, can provide the recovery many are currently missing.

If you’d like to learn more about how myofascial dysfunction affects injuries, mimics pathologies, and prevents full recovery, the evening Advanced Neuromuscular Therapy Programs in Studio City and Ontario are beginning in April. Contact an Admissions Representative to begin your continuing education journey today.

1Sterling M. Whiplash-associated disorder: musculoskeletal pain and related clinical findings. J Man Manip Ther. 2011;19(4):194-200. doi:10.1179/106698111X13129729551949

2Fernandez CE, Amiri A, Jaime J, Delaney P. The relationship of whiplash injury and temporomandibular disorders: a narrative literature review. J Chiropr Med. 2009;8(4):171-186. doi:10.1016/j.jcm.2009.07.006

3Simons, DG, Travell, JGSL. Myofascial pain and dysfunction. The trigger point manual. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer, 2019.

Get the details about NHI’s Advanced Neuromuscular Therapy Program today. Complete this form to connect with an Admissions Representative.