The Neuromuscular Role of the Abdominals in Low Back Pain

The Neuromuscular Role of Anterior Muscles in Low Back Pain

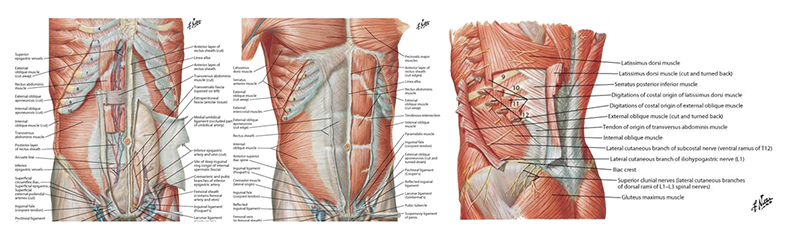

The lumbopelvic region’s stability and mobility rely upon the relationship between the thoracolumbar fascia, the fascia lata, the abdominal fascia systems and all their related musculature. Many therapists feel adept with working on the posterior aspect of the body for lower back pain symptoms; we are going to focus on the role of the abdominal fascia and musculature and present the importance of addressing the anterior musculature for low back pain.

Abdominal Musculature and Fascia

All of these structures attenuate, or disburse, the forces placed on our lumbar spine from forces travelling down through our trunk and up through our legs. The muscles produce forces that “pull” on the fascia, and the muscles that are encased by the aponeurosis are able to place a “pushing” force due to their expanded girth went contracting. The muscles that provide “pull” on the fascia are the external oblique, internal oblique, transverse abdominis, pectoralis major, and serratus anterior. One sole muscle provides “push” onto the abdominal fascia, and that is the rectus abdominis.

By focusing on the anterior muscles, here’s a quick chart reviewing the muscles and their actions:

| Muscle | Action/Function |

| External Oblique | • Flex the vertebral column by bringing the thorax closer to the pelvis • Flex the lumbosacral junction by posteriorly rotating the pelvis • Compress the abdominal viscera • Increase tensile force to abdominal fascia • Rotate thorax to contralateral side |

| Internal Oblique | • Compress the abdominal contents • Increase tension to thoracolumbar fascia and abdominal fascia • Flex the vertebral column by bringing thorax closer to pelvis • Rotate thorax in same direction as opposite oblique |

| Transverse Abdominis | • Compress the abdominal contents • Increase tension to thoracolumbar and abdominal fascia |

| Rectus Abdominis | • Flexes the thorax on the pelvis • Upward tilt of pelvis • Fills rectus sheath |

By reviewing this table, we also want to remember the functions of the abdominal wall which are:

Provide anterior and anterolateral structure to trunk cylinder

Provide anterior and anterolateral structure to trunk cylinder- Increase tension in thoracolumbar and abdominal fascia

- Check anterior shear via control of pelvis in sagittal plane

- Control rate and amplitude of torsion to lumbar spine

- Control relationship of abdominal wall to thorax

- Increase compression at sacroiliac joints and pubic symphysis

The external oblique is the most superficial abdominal wall muscle. This muscle interdigitates with the latissimus dorsi muscle and the upper five rib attachments interdigitate with the serratus anterior. The fibers of the external oblique are oriented in a downward and diagonal direction to attach with the abdominal aponeurosis, the linea alba, and the anterior portion of the iliac crest.

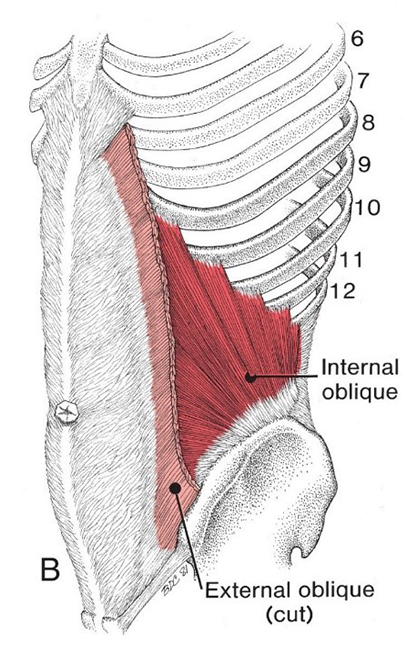

All the fibers of the internal oblique attach onto the lateral half of the inguinal ligament, the iliac crest, and the abdominal aponeurosis, the linea alba through the anterior and posterior rectus sheath.

All the fibers of the internal oblique attach onto the lateral half of the inguinal ligament, the iliac crest, and the abdominal aponeurosis, the linea alba through the anterior and posterior rectus sheath.

There is also a medial attachment to the inguinal ligament which attaches to the arch of the pubis and a shared tendon with the transverse abdominis.

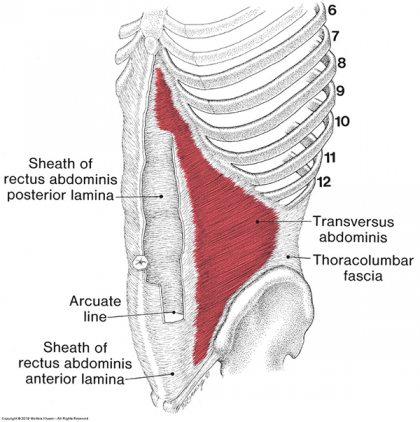

The transverse abdominis run almost horizontally across the abdominal region. It is attached to the linea alba and the rectus sheath which is a fibrous tissue structure that envelopes the rectus abdominis.

The transverse abdominis also attaches to the inguinal ligament, the anterior portion of the iliac crest, the thoracolumbar aponeurosis, the cartilage of the last six ribs and at this location, it interdigitates with the diaphragm.

The transverse abdominis also attaches to the inguinal ligament, the anterior portion of the iliac crest, the thoracolumbar aponeurosis, the cartilage of the last six ribs and at this location, it interdigitates with the diaphragm.

The thoracolumbar aponeurosis is a flat, fibrous structure that serves as an attachment site for muscles on the posterior aspect of the body. This horizontal muscle provides a direct link between the abdominal and thoracolumbar aponeurosis.

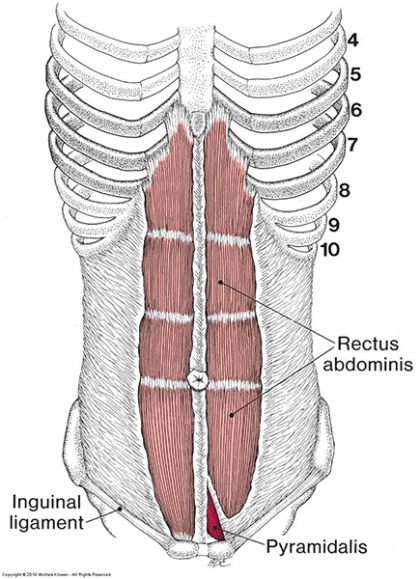

The rectus abdominis is deeper than many consider. It lies beneath the rectus sheath/abdominal aponeurosis. It is attached to the crest of the pubis and travels vertically to the xiphoid process.

The rectus abdominis is deeper than many consider. It lies beneath the rectus sheath/abdominal aponeurosis. It is attached to the crest of the pubis and travels vertically to the xiphoid process.

Both oblique muscles attach to the rectus abdominis via the rectus sheath and impose a lateral compressive force to the sheath. This attachment of the obliques create a biomechanical junction which provides stability to the rectus attachments which allow it function segmentally rather than as one long muscle.

The rectus abdominis is encased within the rectus sheath which is formed by aponeurotic contributions of the transverse abdominis, internal oblique, and external oblique.

Abdominal Functions

- Provide anterior and anterolateral support to the spine

- Typically, the abdominal area is seen as a cylinder. The contraction of the abdominal muscle group along with the pelvic floor, diaphragm, and epiglottis increase the internal pressure which help unload the spine by disbursing and absorbing the trunk forces and ground forces exerted by movement.

- Increase tension to the thoracolumbar and abdominal fascia

- Tension must be exerted upon ligaments, joint capsules, and fascia to stabilize bone segments.

- The contraction of the abdominal muscles will minimize movement within the lumbar spine in the horizontal and frontal planes, while minimizing individual movements between each vertebrae.

- The external oblique attachment to the ribs and the iliac crest provide leverage to the lumbopelvic joints to offer control to axial and lateral movements.

- The shared attachment of the abdominals to the abdominal aponeurosis increase tension which provides support. Specially the rectus abdominis, when contracting, broadens the rectus sheath which increases tension on the abdominal aponeurosis.

- Check anterior shear via control of pelvis in the sagittal plane

- All the abdominals, except transverse abdominis, flex the spine over the lumbosacral junction by posteriorly rotating the pelvis.

- Posterior pelvic rotation decreases the anterior lordotic curve in the L5/S1 area which reduces the anterior shearing of L5 and S1.

- The decrease in lordosis alleviates compression at the apophyseal joint and increases compression of the intervertebral disc.

- The abdominal muscles will reduce the compressive load at the vertebral arch and reduce shear that occurs with any lifting movement.

- Increase compression at the sacroiliac joints and pubic symphysis

- Significant shear forces are concentrated at the sacroiliac joint from both ground and trunk forces.

- Muscle action contributes a great deal to the stability of the sacroiliac joint along with the numerous ligamentous connections.

- The attachments of the obliques create a compressive influence over the sacroiliac joint when they contract. The contraction provides additional stability by bringing the sacrum and the ilia close together. This contraction also increases the compression between the pubic bones at the pubic symphysis

What does this all mean?

Abdominal muscle attachments to the abdominal aponeurosis and the thoracolumbar aponeurosis provide an internal compression in the abdominal cavity. This pressure provides support and reduction of strain on the spine and vertebrae. However, with overly shortened muscles in the anterior region of the body, the force that is meant to keep us standing upright begins to bring the spine into flexion and the pelvis into posterior rotation. The repositioning of the SI joint and the L5/S1 facet can cause multiple concerns:

- Increased compression and shearing of the sacroiliac joint

- Decreased lordotic curve which exerts additional compressive force to the anterior portion of the L5/S1 intervertebral disc

- Increased rotational shearing on the L5/S1 intervertebral disc

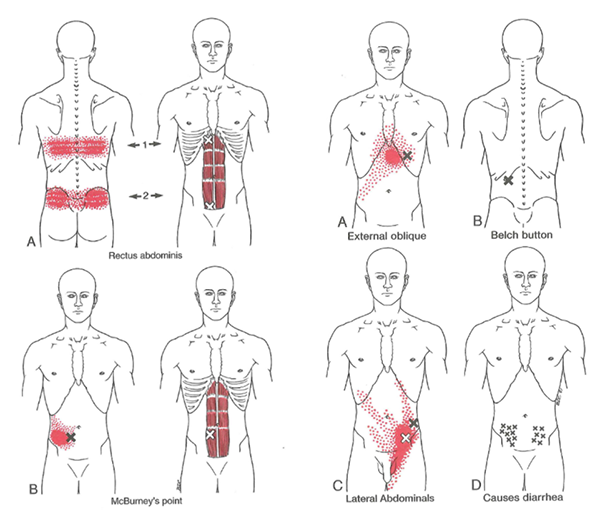

- Development of latent and active trigger points within the abdominal musculature that will refer pain into the posterior aspects of the body, the hip, and the groin

- Somatovisceral and Viscerosomatic pain

- Pain related to movement

- Increased pain with forceful abdominal breathing

- Increased urinary frequency and urgency

- Kidney pain

- Pressure and bloating that is often mistaken as digestive problems

- Heartburn

- Belching

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Pain that is often confused with gallbladder disease or appendicitis

As Neuromuscular Therapists, all of the symptoms are taken into consideration along with the activities of daily living and mechanism of injury of every patient. An in-depth assessment of each patient’s history is necessary to truly understand the appropriate application of Neuromuscular Therapy and the potential need to collaborate with other healthcare providers.

Ready for more? Get all the details about NHI’s Advanced Neuromuscular Therapy Program now. Complete this form to connect with an Admissions Representative.